I read a wonderful article in the Metro recently about post-graduate depression, a subject that has been on my mind quite a lot recently. A few things have contributed to the nostalgia I’ve been feeling, from seeing younger students move into their campus accommodation, to reading about the university experiences of celebrities in their biographies.

DISCLAIMER: I’m lucky enough to not suffer from depression, but the post-uni blues have been hitting me hard this past week. A year ago, I would have been stocking up on things to take to my student house, frantically trying to ‘get ahead’ with reading (i.e. reading the first ten pages of one set text), and spending as much time as I could with the family and in the city that I love.

I keep finding myself lapsing into the old, familiar feeling of starting a new educational year. I think that’s pretty fair – I have, after all, spent seventeen Septembers preparing myself for school. Needless to say then, it’s been a bit of a shock to my system not to have to buy new stationary, uniform, or overpriced books.

Leaving university feels the same as those books that abruptly end. You get to the final page and think, “What? That’s it?”, just as things were getting good, and the shock that there are no more pages leaves you feeling disappointed. As corny as tenuous as this metaphor is, it pretty much sums up how I – and probably many other graduates – currently feel.

I spent most of last night sadly scrolling through photos of the past three years on Facebook, thinking about how much I’ve changed and how I wish I could do it all over again – not because I regret the way I did university, but because I loved it so much. I had huge expectations for university life, and three years just didn’t give me enough time to do everything I wanted.

Of course, I may be looking back with rose tinted glasses. As much as I loved university, I spent at least 30% of the time crying down the phone and screaming into pillows, whilst the other 70% consisted of house parties, late night talks, and wonderful societies.

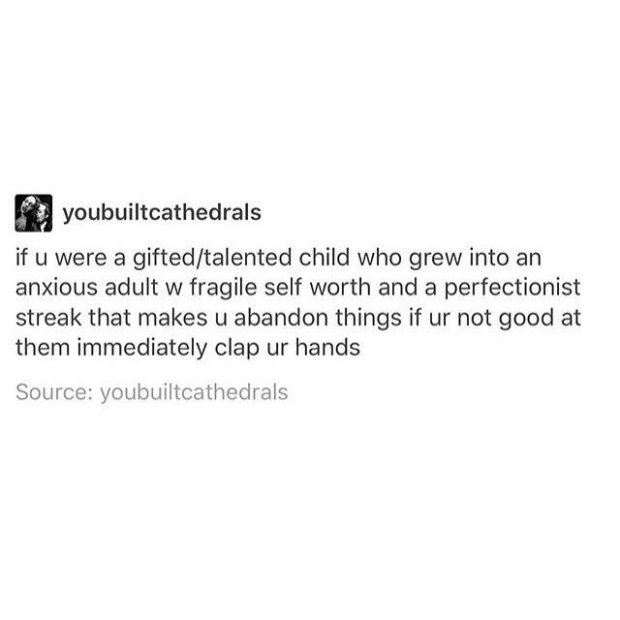

Towards the end of my final year, on the way back from a walk, I boldly told my friend that I was going to forge my own identity after university by doing exactly what I wanted to do, ‘because that’s the best way to be yourself’. I don’t think I was wrong – doing what you want to do instead of managing your actions through fear of judgement is great. But I’m annoyed that I didn’t see how far I had come in those three years. I wouldn’t have admitted that I was shy when I started university, but I was. University managed to change that, even if only slightly. I went from saying about three sentences in conversations to actively seeking out new people to talk to. I started going to the parties I’d avoided throughout secondary school. For once, I started to relax and be myself – even if I felt I wasn’t wholly myself yet.

For some people, university really is the best years of you life, so it’s only natural to feel the post-grad blues when you leave. I just wish I’d been a little more prepared.